If both of Angelina’s legs were showing.

Each gift bag was worth about $60,000. And these got handed out to all the nominees. Reminds me of that line from Withnail & I - Free to those that can afford it. Very expensive to those that can’t.

With no characters to interact with, no enemies to fight, no puzzles to solve, no way to manipulate the environment around you, Dear Esther is guaranteed to spark a thousand hand-wringing debates about what a game actually is. Can a game have none of the elements listed above and still call itself a game? Or is it enough to provide an experience to the player? Come to think of it, if you’re not “playing”, what do you call it?

I guess you could call it exploration. Dear Esther is great at exploration. You explore an uninhabited island, with its beautifully rendered landscapes and scattered clues to the people who once lived there. You explore the story (or stories) being told by the disembodied narrator. You explore the nature of gameplay.

More than anything, though, Dear Esther is about atmosphere. The story being told, the tone of the narration, the haunting soundtrack, the gorgeous visuals. These all add up to a singular atmosphere of loneliness and desolation. The creators have said they were influenced by Tarkovsky’s Stalker – a film that is more about creating an atmosphere than telling a compelling story.

But, although it tries, it can’t escape its game roots. Dear Esther is built with “Source” engine, the same one that powers Half Life 2, and so it’s necessarily constrained in the scope of its ability to tell a story and build the atmosphere it is going for, in much the same way as a book is bound by the constraints of having to tell its story through the medium of static print. As a result, its game-like artifacts are completely out of place in such an anti-game. To prevent you going too far off the prescribed path, Dear Esther uses conventions like invisible walls and insta-death points. Arbitrary rules that people often expect and that sometimes even make sense in a traditional “game”. In something like this, though, they shatter the illusion and the atmosphere.

As a game (if that’s what you decide to call it), Dear Esther a failure. As a story, it falls similarly flat, drip-feeding the brunt of the story through the same kind of cack-handed, painfully oblique passages as we saw in Braid.

As an experience, there’s nothing like it.

Nicholas Felton has released the latest version of his “annual reports” - a collection of all the data that makes up his life. As someone who has trouble keeping track of the movies he’s watched, I’m very jealous of his ability to consistently keep track of this stuff.

After the internet design community started spooging over these things a few years ago, he set up daytum, a website to help people collect these various discrete bits of information and to present them in a “Feltron Annual Report” kind of way. And yet according to the “about” page of the report, (and even according to his account page on daytum), he doesn’t use it himself. I dunno, I just found that interesting.

Spielberg, fresh off Jaws, watching the 1976 Oscar nominations.

“I didn’t get it! I wasn’t nominated! I got beaten out by Fellini!”

If you’ve got 35 minutes to spare, you could do a lot worse than spending it in the company of Ron Gilbert and Tim Schafer, talking about graphic adventures.

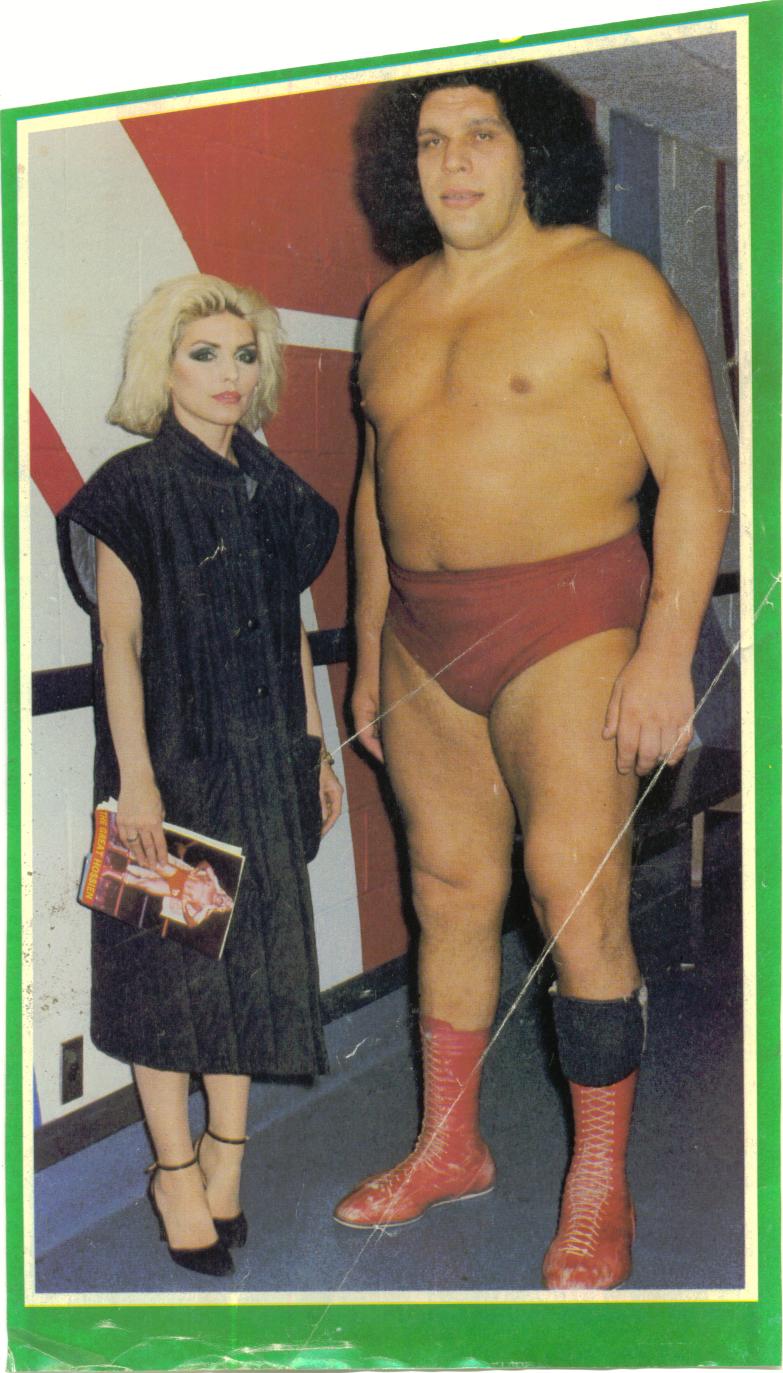

All I need is a giant 70s ‘fro and this could be a picture of me and my wife heading out on a Saturday night.

Scientists are arguing that the 8-hour sleep is unnatural, and that humans naturally fall into a more segmented sleep cycle. In other words, I should be treating every day like I treat Sunday, with a pre-sleep nap.

The problem with Gamification is that it tries to solve a problem that doesn't exist. We already have a universal points system, across all aspects of life, that represents status and is redeemable for real world prizes. **It's called "money."**